Rescuing stranded dolphins

Animals, 20 February 2020stranded (adj.): unable to go home.

This website is for people who want to improve their English: "A strand" is another word for a sandy beach, so stranded really means "on a beach, and can't get back to sea again". For a dolphin, you can say stranded or beached. If we say a person is "stranded", it means they're at work or at an airport and they can't get home because there's too much snow, no public transport, etc.

Whales, dolphins and porpoises sometimes get stranded while they're still alive. You can't really help a 30-tonne whale, but it's often possible to help a healthy dolphin (150-300kg) or a porpoise (80kg) get back to sea.

Whales, dolphins and porpoises are called "cetaceans". They aren't fish; they are warm-blooded and they breathe air. A cetacean can only breathe through the blowhole on the top of its head. It can't breathe through its mouth. Millions of years ago, their ancestors lived on land and looked as if they were half dog, half pony. When they started to live in the sea all the time, they evolved. They lost their legs and most of their leg bones, and they can't move around on a beach. They can't even roll into an upright position if they are lying on one side. If they are stranded, they must wait for the water to come back, or for humans to help.

Cetaceans have always stranded on beaches. There are records of this from Aristotle in 340 BC. They strand individually and in groups ("mass strandings").

There are many reasons for stranding, from a healthy dolphin chasing fish on a falling tide, to an ill or dying whale that does not want to die by drowning at sea. When one individual strands, it is very often ill or dying. When a group of cetaceans strands, they are probably all healthy except for one. That one went to the beach, the others went too because cetaceans that live in groups have very strong social bonds.

The number of strandings is increasing year by year. This indicates that human activity is one factor. Human factors in cetacean strandings include injury by "entanglement" (getting stuck in fishing nets, including "ghost gear" which is abandoned fishing nets); poisoning by pollution; disease and parasites from untreated sewage; and "ship-strike" (impact from a boat or ship). Also, problems with noise. Ship noise over a long period can cause "noise-induced hearing loss" (NIHL or industrial deafness). It seems that very loud underwater noise such as seismic surveys and military sonar can cause mass strandings.

What can you do to help?

| REFLOAT? |

| We all want to be kind, but it's not kind to put every stranded cetacean back in the sea. It probably had serious problems before it stranded. Depending on the species, the location and the condition of the animal, between 15% and 80% of stranded cetaceans can be re-floated. It's always best to call for expert help, and protect the animal until help arrives. The experts can then decide whether to re-float the animal. The experts can also decide how to do this - in particular, how to give it support in the water until it can swim and breathe without help. In rare cases, you can put the animal back in the sea at once BUT ONLY IF: 1) It's small enough to move (see moving a stranded cetacean) AND 2) It seems healthy and active AND 3) Expert help is not available. |

| STABILISE |

| Nearly every time, the best thing you can do for a stranded cetacean is protect and support it until expert help arrives. Reduce its stress; keep it wet; keep the sun off it until the water comes back. Make it more comfortable where it is. When the water comes back, support the cetacean in the water so it can breathe until it's ready to swim again. See Stabilising a Stranded Cetacean. |

| REPORT |

| Contact experts for advice and support. They are probably unpaid volunteers, who have to take time off work and drive a long distance in order to help. They will want to know whether the animal is alive, its condition, its length, what help is available, and how near they can get with a vehicle. If possible, tell them what species it is, because some species are more likely than others to re-float successfully. Photographs will be useful, both to decide what to do and to identify individual cetaceans from the shape of their dorsal fin, scars, colouring, etc. |

| REHABILITATE |

| If a stranded cetacean has health problems, maybe you can give it medical care. This sometimes happens at major aquariums. It helps if you have a large vehicle, lifting equipment, a large salt water tank, plenty of fish, paid professional staff, access to veterinary medication including antibiotics for bacterial infections, and a local veterinarian (animal doctor) with special knowledge of cetaceans. These facilities may be available in a region that has a lot of strandings. Cape Cod in America is the global "hotspot" for cetacean strandings, with a live stranding nearly every day on its 20 km of beaches. (Compare with Ireland, which may have one live stranding per week for its entire 4,000 km of coastline). In the 20 years from 1998 to 2018, the IFAW Cape Cod Stranding Network carried out 5,000 rescues. In 1998, they were only able to re-float 15% of the cetaceans they tried to help. Now they have more experience and more money for veterinary care, and they are able to release nearly 80%. They're experts in stranding science. |

| LET IT DIE WITH DIGNITY |

| If 15% - 80% of stranded cetaceans can be re-floated, that means 20% - 85% can't. They will die on the beach. What can you do if a cetacean is too large to survive stranding, or it stranded because it was already very ill, or seriously injured, or unable to get food? Not much. All you can do is protect it while it dies. A large animal can take a long time to die, so you may need to think about euthanasia (killing it). This is a job for a veterinary surgeon or somebody who is an expert in cetacean anatomy. It will be very difficult and emotional for them, and for the rescuers, and for people who have come to watch. Somebody may also need to think about disposal of the body. |

Hazards for a stranded cetacean

The three species that strand most often in the British Isles are the common dolphin (Delphinus delphis), the striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba) and the pilot whale (Globicephala melas). Refloating common dolphins is often successful, but striped dolphins seldom survive.

Health problems. Stranded cetaceans very often have serious health problems. In fact, a cetacean may strand because it is very ill. It may be dying if: It looks emaciated (very thin), or it has serious internal or external injuries, or it's trembling or shaking, or it's using its tail to keep its head on the beach, or it floats in water without moving much, or it seemed to have no interest in life in the days before it stranded. For example, it may have let kayakers or swimmers come right up to it in the water. A cetacean may re-strand several times after being refloated, and this is not a good sign. Experts recommend refloating a cetacean if it is "viable" (if it seems healthy) but not if it is "compromised".

Emaciated? A healthy cetacean does not have a visible neck (a concavity between the head and the body), and it does not have a concave area on its back.

Serious external injuries? These will be obvious. However, a cetacean can lose a large amount of skin if it lands on sharp rocks, and still be OK.

Serious internal injuries? It is normal for a small cetacean to breathe only once or twice a minute, and it is normal for this breath to be loud and powerful - almost explosive. However, if a cetacean has a lot of blood coming from the mouth or other orifices, that's not a good sign.

Too young to be alone? A baby dolphin has no teeth for the first 3 or 4 months. It needs its mother's milk until it is at least 130 cm long (90 cm for a harbour porpoise), and it needs its mother for protection, socialising and education until it is at least 3 years old. Wild dolphins often stay with their mothers for 6 years. If you can't see its mother, it is probably not kind to put a stranded baby cetacean back in the sea.

If mother and baby ("cow and calf") strand together and the baby dies on the beach, it's important to put the dead baby in the water when refloating the mother. If she doesn't see it and know for sure that it's dead, she will re-strand.

Too much weight. On a beach, a really big cetacean like a 30-tonne whale will be injured by its own weight.

Smaller cetaceans like porpoises and dolphins will still be OK after 24 hours on the beach. However, they may get numb flippers. You know sometimes, if you sit on a hard chair for a long time, you can't feel your legs? And you can't stand up or walk for a few minutes? That's numbness or being numb.

Too much heat. Summer temperatures in direct sun can kill a stranded cetacean in a very short time. Even in cool weather, a dolphin lying on a beach can overheat and die. That's because a body loses heat about 25 times faster in water than in air of the same temperature. Cetaceans have excellent thermal insulation, as if they're in a very thick sleeping bag. They have a higher metabolic rate than land mammals, and they generate a lot of heat internally. Unless the water is very cold, they need to lose heat all the time to keep their body temperature at 37 °C. Cetaceans lose heat from their tail and their fins. A body temperature of more than 42 °C is fatal. (A very small or thin cetacean may get too cold on a beach in winter, and may need protection from wind and rain, especially its tail and fins.)

Too much sun. Cetaceans have thin, dark skin which burns easily. Too much direct sun can make their skin crack and peel. Bad sunburn over a large part of the body could be fatal. Sunburn can happen even on a grey, cloudy day.

Too much stress. Stress makes a big difference to heart rate, respiration, blood pressure and blood chemicals. It reduces the chances of a stranded cetacean surviving. Stranding is stressful anyway. If there are people and dogs around, it is extremely stressful.

Injury. A stranded cetacean may be attacked by dogs, sea birds or people. People sometimes make a lot of noise next to them; sit on them; use them as a children's slide; poke them in the eye; try to put water, beer, cigarettes or bottles down the cetacean's blowhole, or use a knife to cut their initials in its skin.

Not enough water or food. Cetaceans get all the water they need from their food. They are quite big animals, so food and water should not be a problem during the short time one is stranded.

Breathing difficulties. A cetacean breathes only through the blowhole on top of its head. If anything (water, cloth, sand, mud) blocks the blowhole, it can't breathe. A stranded cetacean is probably very weak and may not have much control over its blowhole. When you're putting water on a stranded cetacean, make sure none goes into the blowhole. Cetaceans are "voluntary breathers", so if they are unconscious they don't breathe and they die, which means they must never be sedated by a veterinarian. When in the water, a cetacean has to come to the surface to breathe. If it is weak and has numb flippers after spending all day lying on a beach, it may not be able to swim well for a few minutes, or even a few hours.

Stabilising a stranded cetacean: On land

Don't touch it unless you have to. This is for two reasons: First, to reduce stress on the animal. Second, to avoid disease. It may be very ill, and humans can get diseases such as Clostridium (food poisoning) and fungal infections from cetaceans. Also, humans can give disease to cetaceans.If you have to touch it, wear rubber gloves. Don't touch your face afterwards, especially your mouth or eyes.

Keep quiet and keep away from the head, to reduce its stress.

Don't put your face over the blowhole. Cetacean breath smells bad and could make you ill.

Don't let water get into the blowhole.

Don't stand by the tail - it can injure you.

Don't use the flippers as lifting handles.

An efficient rescue team is divided into 3 different roles:

- A Stranding Coordinator, who makes the decisions.

- The Care Team who stay next to the animal, keep it wet and cool and prevent sunburn; and

- The Response Team who help the Stranding Coordinator assess the situation, decide what to do, find equipment, and liaise with the public, wildlife authorities, coastguard, police and the media. Also, because they're free to move around with spare clothes, Factor 50 sun cream and mugs of hot coffee, they look after the care team.

Remember the Four Ps - Positioning, Palliative Care, Protection, Personal Behaviour:

Positioning.

Protect the blowhole and flippers (pectoral fins). If the animal is lying on its side, roll it upright. Before you roll it, make sure its flippers are pressed close to its body so they are not injured. When it is upright, you may need to put sand or stones under its side so that it stays upright. Dig holes in the sand or stones beneath the flippers so they can be in their natural position.

Palliative care:

Prevent overheating by putting water on it, especially on the tail and fins. Don't pour water onto the blowhole. One person can protect the blowhole with their hands while others are pouring water.

Prevent sunburn by putting wet cloth on it. The perfect thing is white towels or sheets, because they also hold water so they help you keep the animal wet. It's also possible to use T-shirts, a sail or tarpaulin (a strong plastic sheet), seaweed or grass, or even sand or mud. It may be possible to move the animal into the shade; a cliff or a boat will have a good shadow that will protect the animal and the rescuers from sunburn.

Protection.

Protection from getting too hot (or sometimes too cold); from sunburn; and perhaps from dogs, sea birds or people.

This means staying with the animal until it can be refloated, or until it dies. If this is going to be a long time, rescuers will need help, including food, drink, warm clothing, something to sit on, shelter from wind, rain or sun, and a break every few hours. Protection may mean moving the animal to a new location.

Personal behaviour:

Reduce stress on the animal. Have the minimum number of people with the animal. Talk quietly, don't make sudden movements, and try to keep away from its head. Ideally, keep everybody else 30 metres away, and ask dog owners to take all dogs 100 metres away or more. Of course, walkers and local people will be fascinated.

Naturally they'll want to look (they are "onlookers" or "bystanders"). They'll want to come close, take photographs, touch the animal, know what you're doing, help if they can. In reality, you probably can't make them stay 30 metres away. If onlookers think you're not doing enough, they can get very angry. They may put a camera in your face and live-stream your reaction on YouTube. If possible, appoint a diplomatic person as "public relations officer". He or she can tell onlookers what's happening and ask them to help minimise the animal's stress. At least 20% of live stranded animals are not "viable" and will not be refloated. It may be necessary to "put down" or "euthanase" (kill) an animal. It's important to explain this to onlookers before doing it. It's a good idea for the rescuers to wear some kind of uniform - reflective jackets, at least. It makes onlookers feel more confident.

So, now you know what to do and what not to do, what's wrong with the rescue picture at the top of this page? If anything?

Stabilising a stranded cetacean: In the sea

A cetacean that has been on a beach for hours may be very weak and shocked:

- It may not have good control over its blowhole. It will drown if water gets into its blowhole.

- It may have numb flippers, and need to be supported in knee-deep water (say 0.5 metre deep) for several hours to get full use of them.

- It may be too weak to swim. Again, it may need to be supported for several hours.

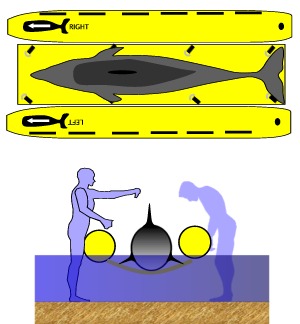

The best way to support a cetacean in the water is with a pair of inflatable tubes like the sides of an inflatable dinghy. They are connected with a tarpaulin (a strong plastic sheet) that goes under the cetacean.

This is called a "rescue pontoon". A rescue team can buy a rescue pontoon from the BDMLR. To see them, do a Google image search on: BDMLR pontoons

When the animal is on the pontoons in the water, it should start to move more strongly and more purposefully. When this happens, it can be taken into deeper water, and the pontoons can be slowly deflated until the animal is floating without help.

Moving a stranded cetacean

When you do a "live stranding" or "first responder" training course, you can learn these techniques from experts, using heavy life-size models of cetaceans. See Get Trained, below.

Do you need to move a stranded cetacean? It's highly stressful for the animal, and quite likely to give one of your team a serious back injury. Maybe just wait for the tide to come back up.

Rolling. You don't roll a live cetacean down the beach, but if a cetacean is lying on its side, you can roll it upright. Also, you can roll it onto its side for a few seconds to look for injuries and check its sex; and you can roll it onto its side for a few seconds to get a plastic tarpaulin underneath it. Don't roll a cetacean so that its flippers ("pectoral fins") bend the wrong way. Press the flippers down, close to the body, as you roll it. A cetacean's flippers are not like our arms. The human shoulder is a very flexible joint so human arms can move in all directions, but flippers don't.

Carrying. If you are in a group that is properly trained and equipped, you can carry a 250kg dolphin a short distance. It's very difficult to move even a small 50kg porpoise. Cetaceans are a difficult shape, they're alive, and they don't have handles! Never pick up a cetacean by its flippers. The best way to carry a small cetacean is to put a plastic tarpaulin underneath it. Put the tarpaulin on the ground next to the cetacean. Roll up the edge that's nearest the cetacean. Roll the cetacean away from the tarpaulin, onto its side. Put the rolled edge of the tarpaulin under the cetacean as far as possible. Roll the cetacean upright again. Then roll it the other way so you can unroll the edge of the tarpaulin.

Dragging. Never lift or drag a cetacean by pulling on its flippers or its tail. If it's on a tarpaulin, you can drag the tarpaulin. This is probably better than trying to carry the animal. If you haven't got a tarpaulin, maybe you can use a coat or a big towel.

Moving with a vehicle. It may sometimes be necessary to put a cetacean in a vehicle and take it to a new location. If the cetacean is on horizontal sand or mud, it may be unable to find the open sea. You may also need to move if the current location is too hot for the cetacean, or if it's too cold, dark, windy, wet or remote for the rescuers.

Some cetacean rescue organisations have a pickup truck with an open back; some have a tarpaulin with straps that can be picked up using the hydraulic arms on a farm tractor with "frontloader" arms.

The photo shows the rescue of a young male dolphin named Igor, who was found by an NBC News film crew in a ditch next to a Louisiana high school. This was after Hurricane Rita in 2005. He weighed 180kg, was carried by 12 people, and had a ride in a US Coastguard helicopter.

English grammar: Active and passive: You can say that a cetacean stranded (active), or that it was stranded or it got stranded (passive). If a cetacean chooses to swim to the beach and stay there, it strands. It's the active voice; the cetacean is the agent. If a hurricane put the cetacean in a ditch like Igor, it was stranded or it got stranded. It's the passive voice; the hurricane is the agent.

Questions: We might ask "How long has the dolphin been stranded?" or "Have any other animals stranded here in the past?"

Do we ever say that a person strands? No, because if a person is at work or at the airport when they want to be at home, the person is not the agent. The agent is snowy weather, or a problem with public transport. We say the person is stranded at work or got stranded at the airport.

Successful refloating?

When a cetacean is refloated, you don't usually know if it was successful or not. The only way to know is if the individual animal is seen again later. In America, the IFAW Cape Cod Stranding Network fits a satellite tag to the dorsal fin when refloating a cetacean. The tags are temporary, and typically stay attached and operational for 3 weeks. Tags are expensive, and fitting a tag requires a research licence, which is not easy to get in Europe.

However, there are two things you can do. You can tie a piece of wool loosely around the base of the animal's tail. Then if it re-strands a few hours or days later, you will be able to identify it. Also, if you take photos of the animal, especially its dorsal fin, it may be possible for observers to recognise it at sea - particularly if it is part of a resident population that is closely studied, as in the Moray Firth or the Shannon Estuary.

A female bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) called "Sandy Salmon", from the Shannon Estuary in Ireland, was stranded on Béal Strand in June 2012. A rescue pontoon was available, but it was a long distance away by road. The dolphin seemed to be fit and healthy, and the rescuers decided not to wait. They used a farm tractor with a large transport box on the back to lift her off the sand and put her back in the water. Since then, she has been seen many times by dolphin-watching tours in the Shannon. Even better, she soon had a baby (a "calf"), which was named "Muddy Mackerel".

In May 2016, another female bottlenose dolphin called "Spirtle" was stranded on mud-flats for 24 hours in the Cromarty Firth, next to the Moray Firth in Scotland. Again, it seems she just made a mistake while chasing fish in shallow water on a falling tide. She got very badly sunburned before a tourist saw her. Rescuers from the SSPCA and BDMLR put wet towels on her back. The tide was falling when they arrived, and it was another 10 hours before there was enough water to float her. As the tide came back in, they put her on a rescue pontoon to recover, and walked her towards deeper water before releasing her. Many people thought she would die after being stranded for so long and getting so sunburned, but she didn't. New skin grew on the burned part, but the new skin was white. That made Spirtle very easy to recognise. In July 2019 she and five other members of her group were seen in Tralee Bay, south-west Ireland. In December 2019, she was seen back home in the Moray Firth.

Stay safe yourself: Injury and Disease

More than half of people who work with dolphins have been injured by them, and more than half of those injuries were serious (source: Wildlife Health Center, University of California, Davis, 2004). Cetaceans are very strong, and a stranded cetacean is highly stressed. Even a dying whale can smash a boat to pieces. Stay away from the tail, don't put your hands in a cetacean's mouth, and never touch its eyes or blowhole.

You can give diseases to animals, and you can catch diseases from animals. Don't touch a cetacean more than you have to, and wear gloves if possible. Again, never touch its eyes or blowhole. Try not to touch your face, mouth or eyes after touching a cetacean, until you have washed your hands with soap and water. A cetacean's breath usually smells horrible and contains an aerosol of bacteria, especially if it is ill or dying. Try not put your face above its blowhole.

Stay safe yourself: Manual handling

What's the most common, serious, permanent injury that humans get at work? It's a low back injury. The classic situation is where something unusual is happening at work. There are boxes or tools on the ground for people to fall over; and people who have no "manual handling" training, and who normally spend all day sitting at a desk, suddenly have to lift big, heavy objects.

That's exactly the situation when volunteer rescuers are helping a stranded cetacean.

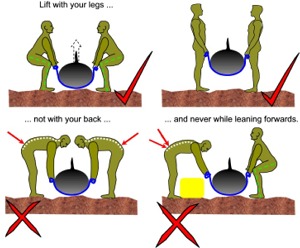

When you lift a heavy object, especially if you are standing on rocks or sand, it is essential to follow basic rules for "manual handling":

- Don't lift more than 25kg, unless you often lift heavy things. Share the load with somebody else.

- Don't carry more than 12kg across a rocky beach. You may trip. Share the load with somebody else.

- If there's a 20kg compressed air cylinder to carry down the beach, that is a two-person lift.

- If there's a 250kg dolphin to carry 1 metre, that is a ten-person lift, or twelve people if possible.

- Lift with your knees, not with your back. See picture.

- Don't twist or bend sideways while lifting a heavy load.

- NEVER lift a heavy object while bending forward with your arms extended in front of you. See picture.

- Avoid "shock loads". Shock loading happens when your lifting partner trips or lets go unexpectedly.

- Plan the lift to do it safely. Remove all loose equipment and rocks from the lifting area. If you're lifting a 250kg dolphin onto a stretcher or a sledge, make sure the stretcher is in front of the dolphin, not beside it. That way, nobody has to climb over the stretcher while holding the dolphin.

- One person should direct the lift. Make sure everybody else is listening to him or her and looking at him or her. Make sure everybody is ready before lifting.

The tide

Tides are changes in sea level.

Some places don't really have tides. If you're from the Mediterranean or the Baltic, you need to read this section before you go on holiday to the Atlantic!

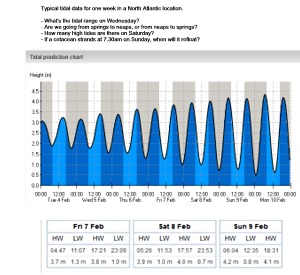

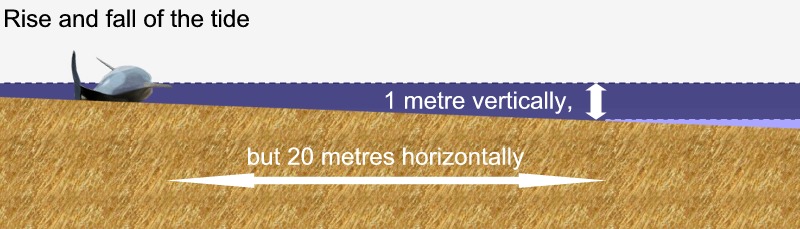

Sea level goes up and down on a "tidal cycle" of 24 hours 50 minutes. The vertical distance between high tide and low tide is called the "tidal range". In the diagram below, the tidal range is 1 metre. The tidal range in most parts of the world is less than 1.5 metres, but in the Atlantic and on the Pacific north-west coast of north America, it's often 3 metres or even 6 metres.Or even 15 metres in a few places.

In the Atlantic, there are two high tides and two low tides in that time. That means you have a high tide, then about 6 hours later it's low tide, and 6 hours after that it's high tide again. So, if an Atlantic dolphin is stranded an hour before low tide (or "low water"), the water will come back an hour after low tide. But if a dolphin is stranded at high tide, it will be 12 hours before the tide comes back.

Some high tides are higher than others. "Spring tides" can be a metre higher and lower than "neap tides". Spring tides happen every 28 days, with neap tides 14 days after every spring tide. The tidal range is much bigger at spring tides. For example at Dartmouth in England, the tidal range at neap tide may be 1.7 metres but two weeks later at spring tide, 5.3 metres. (Spring tides happen all year round, not just in spring!) So, if a cetacean is stranded at high tide during spring tides, the next high tide may be a little lower, and the next high tide a little lower than that.

On a typical sandy or muddy beach, as sea-level goes down 3 (or 6) metres, it may expose 100 or 200 metres of beach. In other words, it can easily be 200 metres from a stranded cetacean to the nearest water.

In the diagram above, the gradient of the beach is 1:20 or 5%. Strandings often happen on very, very flat beaches or mudflats with a gradient more like 1:100 (1%) where the sea may go out 2000 metres or more. These places are rare and they're obvious - you will see a huge area of sand or mud at low tide. For example, the Solway Firth and Morecambe Bay in the UK, and Mont St Michel in France. They can be dangerous for humans and dolphins. They're dangerous for humans for two reasons. First, because these flat areas often have soft areas where people and vehicles can get stuck. Second, because the tide can come back in very, very fast. On 5th February 2004, 23 people (and their vehicle) drowned on the sands of Morecambe Bay, because the tide came in faster than they expected.

Very flat beaches are dangerous for cetaceans for two reasons. First, the water goes out very fast, so it's easy to get stuck. Second, it's very difficult to know which is the way to the sea.

The good news is that the tide is predictable. You can find out the times of high tide, low tide and the tidal range for that day online, for example using EasyTide, or you can buy a little book of "tide tables" and keep it in your car.

The experts

Helping live stranded cetaceans

Many countries and regions have their own wildlife rescue organisations. If not, maybe a marine aquarium, the fire brigade or lifeboat service will help. If the country is both rich and has a lot of strandings, these may be professional groups with government funding. However, most rescue organisations are voluntary, so they use their own time, money, vehicles and equipment. Here are some, or click here for a map of widlife rescue centres in western Europe. Most of the centres on the map rescue only birds and land mammals.

- Belgium. See Netherlands

- Denmark. Denmark is infamous for the "Grindadrap" whale and dolphin killing festival on the Faeroe Islands, when 800 pilot whales and dolphins are killed for fun and to eat. Oh, I'm sorry, they're killed because it's traditional and cultural. They also enjoy shooting porpoises with shotguns. Denmark does not seem to have any whale and dolphin rescue organisations.

- France. The France National Stranding Network (RNE, Réseau National Echouages) is run by the Observatoire PELAGIS. Report live and dead strandings to www.observatoire-pelagis.cnrs.fr. Both the fire brigade (sapeurs-pompiers) and the lifeboat service (la Société nationale de sauvetage en mer) rescue cetaceans from time to time, and there are several marine national parks and large marine aquariums.

Selon l'Observatoire PELAGIS: "Nous contacter pour toute prise de décision et ne pas paniquer, rester calme, les secours arrivent ! Eviter de manipuler inutilement l’animal pour éviter de le stresser ou le blesser d’autant plus qu’un animal sauvage peut chercher à se défendre (coups, morsures...). Eviter les attroupement, l’agitation et le bruit. Ne pas tenter de remise à l’eau sans l’aide personnes qualifiées (RNE ou services de secours). Humidifier la peau de l’animal en couvrant son dos et ses flancs de linges humides, ne jamais couvrir, ni arroser son évent (orifice de la respiration au sommet de la tête). Si les linges font défaut, arrosez prudemment l’animal. Ne jamais tirer sur les nageoires". - Germany. See Netherlands

- Great Britain: BDMLR (British Divers Marine Life Rescue). Since 1988. "A voluntary network of trained marine mammal medics who respond to call-outs from the general public, HM Coastguard, Police, RSPCA and SSPCA and are the only marine animal rescue organisation operating across England, Wales and Scotland. We have a wide range of equipment strategically placed throughout the country to deal with strandings of marine animals, oil spills, fishing gear entanglement and in fact any type of marine animal in trouble. This includes rescue boats, equipment trailers, whale and dolphin pontoon sets, a whale disentanglement kit and each area has a medic kit with essential supplies."

- Great Britain: CRRU (Cetacean Research & Rescue Unit). "The only full-time, specialist emergency response team of marine researchers dedicated to whales, dolphins and porpoises in Scotland and the UK. The fully trained team of cetologists, veterinarians and volunteers are on standby 24 hours a day, throughout the year, with specialised rescue equipment, medical diagnostics and veterinary supplies to assist sick, injured and live-stranded cetaceans in trouble. The veterinary team also provides international support and advice for stranding situations regarding first aid, veterinary treatment protocols and refloatation procedures as required."

- Ireland: IWDG (the Irish Whale & Dolphin Group). Since 1990. Research at sea and on land, campaigning, education and cetacean rescue teams, with local groups in Galway and seven other locations around the coast of Ireland. "In case of a stranding, telephone the nearest National Parks and Wildlife Service ranger."

- Netherlands: SOS Dolfijn, www.sosdolfijn.nl. They rescue small cetaceans, and rehabilitate porpoises before release. "The Dutch stranding network for marine mammals consists of various NGO’s, research institutes and individuals. SOS Dolfijn represents a rescue organisation for small cetaceans and is an advisory body for the government and other party’s in the event of a live whale stranding on the Dutch coast and in surrounding countries."

- Portugal. Most strandings in Europe are in Portugal and Galicia (see Spain).

For Portugal, report strandings to the Polícia Marítima.

Sociedade Portuguesa de Vida Selvagem: https://www.facebook.com/socpvs/

CRAM (Centro de Reabilitação de Animais Marinhos): https://www.facebook.com/cram.ecomare/

Zoomarine (Algarve): https://www.zoomarine.pt - Spain.

Andalusia: Equinac, https://asociacionequinac.org

Asturias: CEPESMA (Coordinadora para el Estudio y la Protección de las Especies Marinas), http://www.cepesma.org

Gibraltar: DEHCC (Department for the Environment, Heritage & Climate Change), http://www.thinkinggreen.gov.gi

Collecting data to reduce future strandings

Mass stranding is a mystery; many biologists would like to solve it by getting more information.

There are national organisations that examine living and dead cetaceans, and collect data and samples.

France. Observatoire PELAGIS. www.observatoire-pelagis.cnrs.fr

Germany. See Netherlands

Great Britain

UK generally: CSIP (Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme) is at www.ukstrandings.org.

Scotland: SMASS (Scottish Marine Animal Stranding Scheme) is at www.strandings.org.

Ireland: The Irish Whale & Dolphin Group. Click here for report form.

Netherlands: SOS Dolfijn, www.sosdolfijn.nl.

Portugal: Report strandings to the Polícia Marítima.

Sociedade Portuguesa de Vida Selvagem: https://www.facebook.com/socpvs/

Spain: CEMMA (Coordinadora para o Estudo dos Mamíferos Mariños). http://www.cemma.org

The minimum information to collect is the species, numbers, sex, size and location, but each national or regional organisation has its own checklist. For example (suggested by the CRC Handbook of Marine Mammal Medicine):

Environmental factors:

- Previous strandings at this site (historical perspective).

- Coastal and underwater landscape (a lot of strandings involve deep-sea species landing on sandy beaches with a very shallow gradient, which may be hard for them to sense). Beach type, beach gradient, presence of barrier islands, sandbars, etc, from direct observation and from a large-scale marine chart.

- Geomagnetic maps of the area (navigation by cetaceans is a mystery, but they probably use the Earth's magnetic fields. Geomagnetic maps are available for some parts of the world).

- Solar storm (can cause geomagnetic anomalies).

- Natural events (landslides, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes).

- Tide, sea surface temperature, salinity, fronts, currents, etc.

- Storms within the last few weeks.

- Fisheries data on recent fish catches.

- "Red tides" and other harmful algal blooms.

- Die-offs of other species in the recent past.

Social factors in mass strandings:

- Species.

- Is it possible to identify the group's leader?

- Group demographics (age and sex).

- Ratio of live to dead animals.

- Cow-calf pairs.

Human factors ("anthropogenic factors"):

- Entanglement (getting caught in fishing nets or other fishing equipment).

- Ship-strike (when a ship hits a cetacean).

- Shooting (with rifle, shotgun, spear or crossbow).

- Acoustic events (seismic surveys, gas exploration, military use of explosives, etc).

- Presence of naval ships or submarines in the area. The US Navy apparently accepts that intensive use of sonar during military exercises sometimes causes mass strandings, probably by making panicked cetaceans temporarily deaf.

- Proximity to naval weapons research or testing facility.

Health factors:

It helps living cetaceans if dead animals are thoroughly examined for diet, reproductive status, health problems and age (by cutting a tooth in half). This is a post mortem examination. Tissue and fluid samples may be taken. For humans, this is called an "autopsy"; for animals, it's called a "necropsy".

Cetaceans in the Atlantic have recently had big problems with morbillivirus and toxoplasmosis. Health problems may include pneumonia; infections from bacteria, viruses or fungi; deafness caused by toxins, parasites or ship noise; intestinal obstructions; and pollution by chemicals.

Get trained

Many organisations in different countries do short training courses for people who want to help stranded cetaceans. They might be called "live stranding" or "first responder" courses.

In the British Isles, there are:

- BDMLR in the UK (one day course, venues all round the UK, £90)

- CRRU in Scotland (free training but only in Banff).

In Ireland there is:

- IWDG (one day course, venues all around Ireland, €50).

Another great organisation

The Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust at www.hwdt.org does research on land and at sea, with its sailing yacht Silurian.

HWDT also does campaigning, outreach and education: "We work directly with local communities to ensure whales, dolphins and porpoises are protected and valued throughout Scotland’s west coast."

More reading

- Face to Face with a Beached Whale (booklet with a lot of practical advice about stranded dolphins and porpoises). Simon Berrow and others, 2017, published by the Irish Whale & Dolphin Group. Buy from www.iwdg.ie website.

- Marine Mammals Ashore: A Field Guide for Strandings, Geraci and Lounsbury, 2nd edn 2005, published by the US National Aquarium, Baltimore, ISBN-13: 9780977460908. Complete book available free on the Internet Archive at https://archive.org. CLICK FOR FREE DOWNLOAD.

- CRC Handbook of Marine Mammal Medicine: Health, Disease, and Rehabilitation, Gulland, Dierauf and Whitman, 3rd edn 2018, pubished by CRC Press, ISBN-13 9781498796873. £140.00

Picture credits

- Banner photo, dolphins in the Bay of Biscay. Rab Lawrence, CC BY-SA 2.0

- Dolphin on rescue boat, David Mark on Pixabay.

- Stranded spinner dolphin, Texas. Terry Ross, CC BY-SA 2.0

- Stranded common dolphin, Kill Devil Hills. Bobistraveling, CC BY 2.0

- Rescuing Igor, Marion Doss, CC BY-SA 2.0

- Other graphics: Nicholas of Linguetic and OnePlanet, all rights reserved.